NEW YORK (AP) — When was a child growing up in New York's Little Italy, he would gaze up at the figures he saw around St. Patrick's Old Cathedral.

“Who are these people? What is a saint?” Scorsese recalls. “The minute I walk out the door of the cathedral and I don’t see any saints. I saw people trying to behave well within a world that was very primal and oppressed by organized crime. As a child, you wonder about the saints: Are they human?”

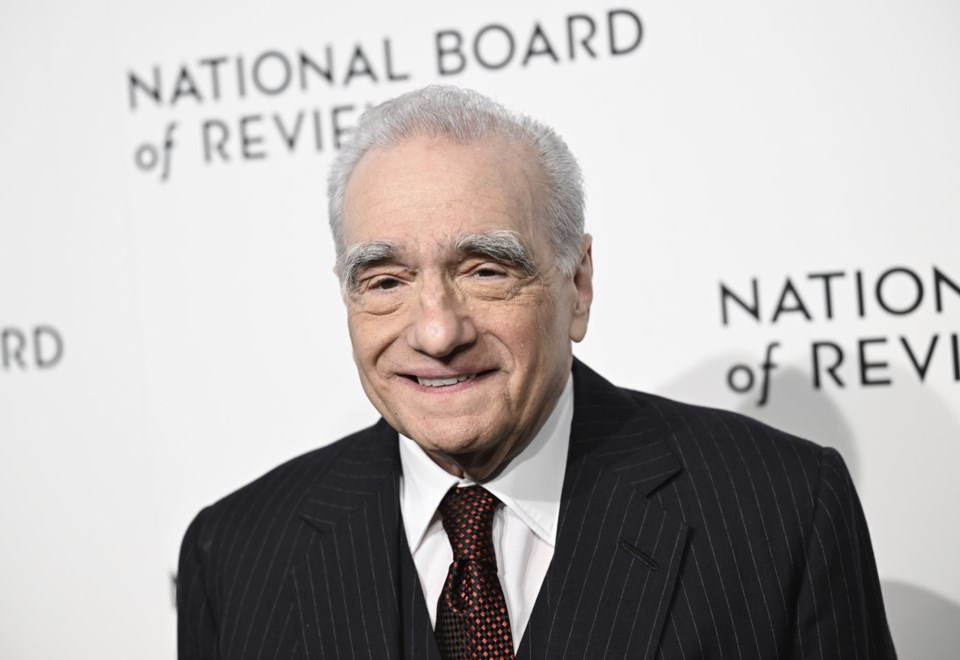

For decades, Scorsese has pondered a project dedicated to the saints. Now, he's finally realized it in an eight-part docudrama series debuting Sunday on Fox Nation, the streaming service from Fox ߣÄĚÉçÇř Media.

The one-hour episodes, written by Kent Jones and directed by Matti Leshem and Elizabeth Chomko, each chronicle a saint: Joan of Arc, Francis of Assisi, John the Baptist, Thomas Becket, Mary Magdalene, Moses the Black, Sebastian and Maximillian Kolbe. Joan of Arc kicks off the series on Sunday, with three weekly installments to follow; the last four will stream closer to Easter next year.

In naturalistic reenactments followed by brief Scorsese-led discussions with experts, “The Saints” emphasizes that, yes, the saints were very human. They were flawed, imperfect people, which, to Scorsese, only heightens their great sacrifices and gestures of compassion. The Polish priest Kolbe, for example, helped spread antisemitism before, during WWII, sheltering Jews and, ultimately, volunteering to die in the place of a man who had been condemned at Auschwitz.

Scorsese, who turns 82 on Sunday, recently met for an interview not long after returning from a trip to his grandfather's hometown in Sicily. He was made an honorary citizen and the experience was still lingering in his mind.

Remarks have been edited for clarity and brevity.

AP: What made you want to make “The Saints”?

SCORSESE: I go back to my early childhood and respite and the sanctuary I found in St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral. Not being able to play sports or be a tough guy in the streets. And, you know, the streets were pretty tough down there. I found a sanctuary in that place. It's now a basilica. The first Catholic Cathedral in New York in 1810, 1812. It figures in “Gangs of New York.” The Know Nothings and anti-immigration groups attacked it in 1844. Archbishop Hughes fought back. It’s a place rife with history. In this contemplation, I was curious about these figures, these statues, and what they represented. They had stories.

AP: Did you understand them then or did they seem divine?

SCORSESE: It took time to think about that and to learn that, no, the point is that they are human. For me, if they were able to do that, it’s a good example for us. If you take it and put it in a tough world — if you’re in a world of business or Hollywood or politics or whatever — if you’re grounded in something which is a real, acting out of compassion and love, this is something that has to be admired and emulated. They make mistakes. I found that by over-appreciating that person, it almost takes you off the hook. “At least there’s someone doing it.” Well, what about you? Dorothy Day was quite something but she knew: Don’t put that label on me because it gets everyone off the hook.

AP: Some were surprised that you’re releasing “The Saints” with Fox Nation. What led you to them?

SCORSESE: I’ve been wanting to do this for years. I tried doing this back in 1980 with RAI Television in Rome. Then it fell apart and I put the energies into “The Last Temptation of Christ,” “Kundun,” — the ones that were obviously in that realm of what you may call spirituality.

Here, they came by and it was actually going to happen. I said, “Yeah, I’ll go with this.” They said, “This is the outlet.” I said, “Alright, as long as we have the freedom to express what we want.” They went with the scripts. They went with the shoot. They went with the cuts. Now what I think is: Do we take these thoughts or expressions and only express them to people who agree with us? It’s not going to do us any good. I’m talking about keeping an open mind.

Shooting in Manhattan and shooting in Oklahoma (where “Killers of the Flower Moon” was filmed) are two different things. Being around people on a farm that is one-tenth bigger than the size of Manhattan is very different than being on 63rd Street. You begin to see the world from how they perceive it. Just to understand what daylight and nighttime means in rural areas. That was a revelatory experience being out there for that long.

AP: You've made directly religious films like “Silence" and “The Last Temptation of Christ," but I wonder how you see the role of your faith in filmmaking. How are God and cinema related to you?

SCORSESE: The filmmaking comes from God. It comes from a gift. And that gift is also involved with an energy or a need to tell stories. As a storyteller, somehow there’s a grace that’s been given to me that’s made me obsessive about that. The grace has been through me having that ability but also to fight over the years to create these films. Because each one is a fight. Sometimes you trip, you fall, you hit the canvas, can’t get up. You crawl over bleeding and knocked around. They throw some water on you and somehow you make it through. You go to another. Then you go to another. This is grace, it really is.

For me, it’s not that cinema is a god. It’s the expression of God. Creativity is the expression of God. Something happens in you when it clicks, when it works. Not everybody thinks it works, but maybe you do. But something happens and there’s no way of expressing that, except that it’s a gift. For me, it’s a gift to experience and existing for that moment. So it comes through cinema. It comes through movies. Even a commercial because commercials are not easy. You have to tell a story in less than 45 seconds. My last picture was three hours, 15 minutes. (Laughs) Come on!

AP: In the year since you've juggled a few different options for your next feature. Where are you right now? Do you expect “The Life of Jesus,” from the Shusaku Endo book, to be your next film?

SCORSESE: It’s an option but I’m still working on it. There’s a very strong possibility of me doing a film version of Marilynne Robinson’s “Home,” but that’s a scheduling issue. There’s also a possibility of me going back and dealing with the stories from my mother and father from the past and how they grew up. Stories about immigrants which tied into my trip to Sicily. Right now, there’s been a long period after “Killers of the Flower Moon.” Even though I don’t like getting up early, I’d like to shoot a movie right now. Time is going. I’ll be 82. Gotta go.

AP: Are you being guided at all differently in that choice?

SCORSESE: You’re guided by: Is it worth doing at this late stage in your life? Can you make it through? Is it worth your time? Because now, the most valuable thing aside from people I love, my family, is time. That’s all there is.

AP: Have you seen anything lately that you’ve liked?

SCORSESE: Some older ones I’ve been watching. There was one film I liked a great deal I saw two weeks ago called It really was emotionally and psychologically powerful and very moving. It builds on you, in a way. I didn’t know who made it. It’s this Jane Schoenbrun.

AP: Any older films?

People should see over and over again. I think that’d be important.

AP: Do you have any strong feelings about the election?

SCORSESE: Well, of course I have strong feelings. I think you can tell from my work, what I’ve said over the years. I think it’s a great sadness, but at the same time, it’s an opportunity. A real opportunity to make changes ultimately, maybe, in the future, never to despair, and to understand the needs of other people, too. Deep introspection is needed at this point. Action? I’m not a politician. I’d be the worst you could imagine. I wouldn’t know what actions to take except to continue with dialogue and, somehow, compassion with each other. This is what it’s about.

Jake Coyle, The Associated Press