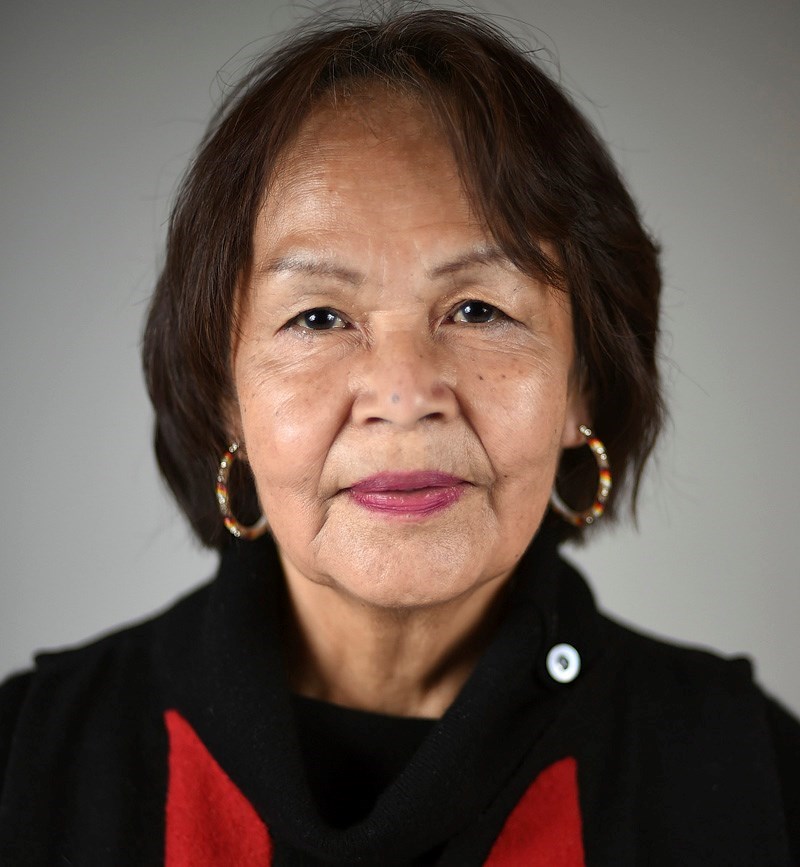

The 70-year-old champion of Indigenous rights and culture was also gracious with the time she gave to people like me, who wanted to learn more about her life and what it was like to be

We met five years ago on the rooftop deck of the Woodward’s building in the Downtown Eastside, where she lived in a suite with her daughters. I recall it being a sunny afternoon, with the sounds of the street reverberating up to the bench we shared.

It was an educational, emotional few hours.

Lillian was a survivor of the Christie residential school on Meares Island near Tofino. She was also a witness to and victim of domestic violence. The details she shared were raw and horrifying.

Counselling, therapy and treatment had helped, she said, noting that opening up about such darkness in a cultural sensitivity training session that she and other Indigenous people led for Vancouver police officers also assisted in the healing.

But the hurt, as she said on that day, was still there.

“It just takes work every day — every day it takes work,” Lillian said. “It’s a life-long process. I told myself I really don’t want to be a bitter old woman. I want to be able to have my children and grandchildren remember me as a loving, kind mother and grandmother.”

And she was, by the accounts of her daughters posted on this week to help with funeral arrangements for their mother, who died Oct. 30 in hospital. The cause of death was not released.

“Our mother was so caring and giving to the community and many organizations,” wrote Celeste Howard, her eldest daughter. “She was truly a strong Aboriginal advocate, a strong Nuu-Chah-Nulth woman, a beautiful and memorable Mowachaht/Muchlaht woman.”

The announcement of Lillian’s death on social media led to an outpouring of condolences and best wishes to her family. Police, politicians, community leaders and others, including the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, where Lillian worked for several years, shared in the grief.

“UBCIC mourns the loss of Lillian, who leaves behind an incomparable legacy of hope and inspiration for those fighting to end systemic discrimination, and who was the pillar of her community — an endless source of wisdom, strength, and kindness,” the organization said in a news release. “We offer our deepest condolences to her beloved family, friends and community members.”

City council this week also held a moment of silence to remember Lillian, who was an enthusiastic volunteer for several years with Vision Vancouver, the party that dominated city hall for a decade.

Her resume included work as executive director of the Aboriginal Policing Centre, as an Aboriginal support worker in Vancouver schools and staff member at the WISH drop-in centre for women.

She also volunteered at the Aboriginal Front Door Society and was tied to a program at B.C. Women’s Hospital and Health Centre for Indigenous patients and families.

Her activism was legendary, with she and a group of Indigenous women in the 1980s occupying the downtown Indian Affairs office for 28 days to protest inadequate housing, poor living conditions and poverty in B.C.

A decade ago, she went on a 31-day hunger strike in support of Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence’s hunger strike in Ottawa, whose protest was aimed at getting a meeting with then-prime minister Stephen Harper.

As our conversation came to a close back on that day in 2016, Lillian was full of hope about the future for Indigenous people, despite the history of colonialism and continued racism present in everyday life.

She said there was a real need to keep fighting for a better Vancouver, a better Canada.

Lillian urged more Indigenous people to get involved with the broader community, to stand tall and be proud of who they are and what they can offer in relationships with non-native groups, diverse communities and political bodies.

“You can make a difference,” she said. “Sometimes, it can take years. But I’m not doing this for me. It’s for my children and my grandchildren.”

Lillian’s funeral is scheduled to occur Nov. 9. Details are expected via the GoFundMe page set up in her name.