Gas stoves in several Vancouver, B.C., homes have been found to produce the most toxic benzene emissions of 17 North American cities analyzed in a new study.

The , published in the journal Environmental Research Letters Tuesday by researchers from Stanford University and the research institute PSE Healthy Energy, examined more than 500 unburned natural gas samples collected in 2021 and 2022.

After testing for hydrocarbons and dozens of hazardous air pollutants, the researchers found 97 per cent of the samples contained benzene — a toxic compound that through has been found to cause blood cancers like leukemia.

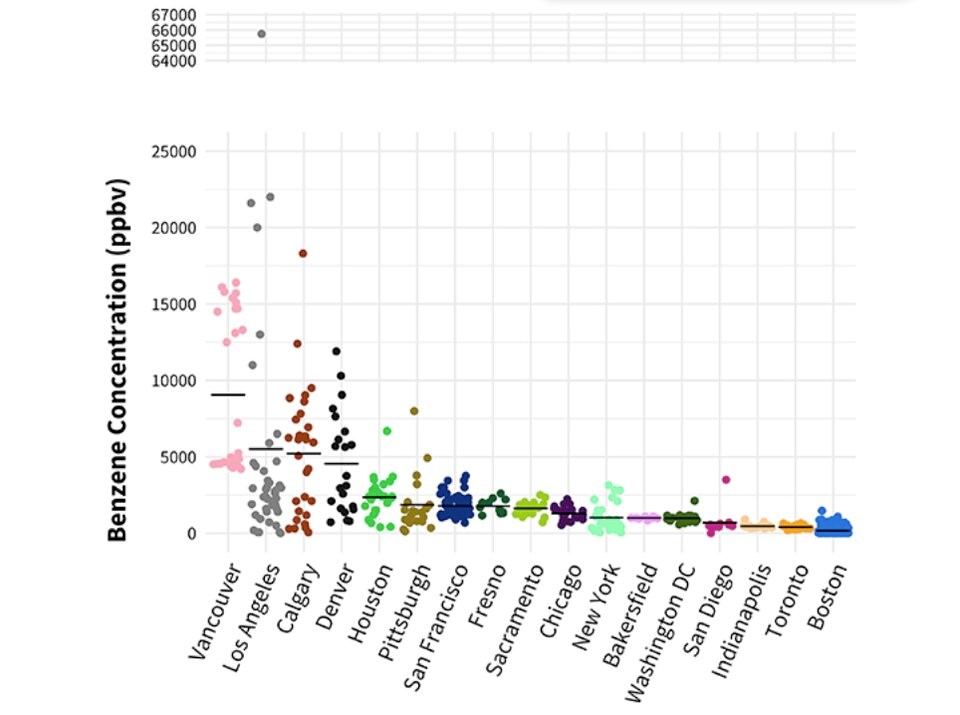

But the cities varied wildly in how much benzene was in their gas systems. Samples from Vancouver were found to have mean benzene concentrations nearly double that of Los Angeles, Calgary and Denver, the next three high-benzene cities, and 50 times higher than Boston, the city with the lowest concentrations.

Drew Michanowicz, a senior scientists at PSE Healthy Energy in Boston and the study’s supervising author, said because benzene is a known carcinogen, there are really no safe exposure levels.

“It's the most toxic of the compounds that we find in natural gas,” said Michanowicz. “So, yeah, I would say it was kind of surprising to find the levels that we found in Vancouver.”

Michanowicz said the cities in the study were chosen based on population size, geography and proximity to the oil and gas industry. Past studies had shown that Californian cities had particularly high levels of benzene, and Michanowicz said the team was curious if those numbers were reflected up the coast in Vancouver.

Dave Risk, an emissions measurement scientist and head of St. Francis Xavier University’s Flux Lab in Nova Scotia, said the big gaps in benzene concentrations likely comes from different regions sourcing their gas supply from different production reservoirs.

Geologic processes that have played out across millions of years mean the makeup of gas in northeastern B.C. and Alberta will be different than that found on east coast of the U.S., said Risk, who didn’t take part in the study.

“Natural gas is a little bit like a soup,” he said. “Depending where we're pulling from, we're going to have naturally different benzene concentrations in the natural gas.”

A smelly risk

In each sample, the researchers also measured concentrations of organosulfur odourants, the rotten egg smell gas companies add so people can recognize a gas leak.

Thirteen homes in the study were found to have gas leaks residents failed to smell. That’s a worry for people who have trouble smelling — either due to age or a smelling dysfunction brought on by an illness like COVID-19, Michanowicz said.

“It's the kind of the only safety system that exists,” Michanowicz said. “We really just rely on our individual noses.”

“But in some some samples, we found no detectable odourant at all.”

The study estimates U.S. and Canadian emissions inventories are failing to count 29,000 pounds of benzene emissions through natural gas leakage every year.

Long-term, chronic exposure to all that benzene could lead to higher rates of cancer, and when leaked into the atmosphere, the largely methane gas acts as a greenhouse gas over 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide over 20 years.

Then there’s the very short-term risk: a gas explosion engulfing someone’s home.

Risk said the regulatory targets set to odourize gas are fairly broad, so it’s no surprise their levels varied from city to city. What did surprise him was that they failed to match the concentration of benzene in the gas.

“It is a concern,” said Risk. “The fact that the odourant doesn't entirely protect us is, I'd say, concerning information and something that we would need to pay attention to and that the regulators might want to look at.”

Correction: A previous version of this story stated researchers collected 481 natural gas samples. More than 500 samples, in fact, were collected from 481 homes.