Two of the last three northern spotted owls living in the Canadian wild have been found dead months after they were last seen.

Remains of the two owls, which were released from captivity in the summer of 2022, were found with their transmitters outside their protected area in the Fraser Canyon, according to Chief James Hobart of the Spô'zêm First Nation.

“The two owls flew out of the protected area. So the government is saying one thing about what they're doing to protect the spotted owl, but the spotted owls aren't reading those maps, they're flying right out of that area,” Hobart said.

Nathan Cullen, minister of water, land and resource stewardship, said the cause of the released owls' death is unknown, but could include physical injury, predation, disease or starvation.

Hobart said he suspects the owls got snowed in and ran out of food.

“Think probably they both starved,” he said.

About 40 centimetres tall with dark plumage, dark eyes and no ear tufts, the northern spotted owl ranges from southern B.C. through Washington, Oregon and into northern California. A subspecies of the spotted owl, it was listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act in 2008.

The two dead owls were among three males reared at a breeding centre in Langley, B.C., and released into the old-growth forests in the area last August. The third was returned to the breeding centre where it is recuperating after being hit by a train. The latest two deaths mean there's only .

More 'babysitting' and more protection of old growth required, say critics

The Spô'zêm First Nation has been deeply involved in efforts to recover the northern spotted owl population in Canada. But much of the periodic check-ups are still carried out by government scientists.

Hobart says biologists from the B.C. government’s had last seen the owls safe on Dec. 2, 2022. He said the owls appeared to be eating at the time. But in the months since, the chief says nobody had seen them alive. In early May, a member of his First Nation found the transmitters and decayed remains of the two owls.

“They should have had more babysitting throughout the first year,” Hobart said.

The owls’ deaths come only a couple of months after federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault recommended an emergency order to halt logging on 2,500 hectares of old-growth forest, home to the last known wild spotted owl.

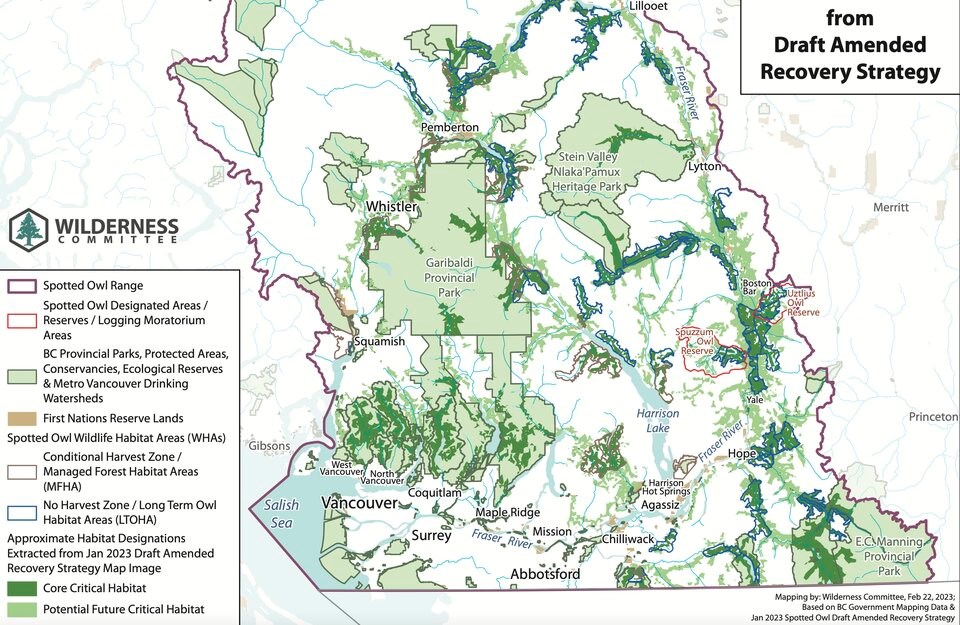

The recommendation, which still needs cabinet approval, would protect two patches of forest near Spuzzum and Utzlius creeks in the Fraser Canyon. Core critical habitat for the northern spotted owl stretches from the Lower Mainland, through the 撸奶社区Valley to Whistler, Pemberton, down the Fraser Canyon and south past Hope.

鈥婽he recommendation to protect two swathes of land near Spuzzum Creek and Utzlius Creek come after an "imminent threat assessment" examined the impact logging had on the owl’s habitat, according to a letter from Daniel Wolfish, director general of the Canadian Wildlife Service’s regional operations directorate.

The threat assessment indicated logging “poses an imminent threat to the survival of the species” and that 2,500 hectares of land in the area have a “high potential to be harvested over the next year,” according to the letter seen by Glacier Media.

Allowing the logging of the two areas would make recovery of the species “highly unlikely,” added Wolfish.

鈥婱inister 'remains confident' in rehab approach

Cullen said the deaths of the two owls was “unfortunate” but that he “remained confident” in the overall approach they were taking to try to bring back the species in the wild.

“Everyone involved in spotted owl recovery in B.C. is saddened by the loss of these two amazing creatures, but releasing captive-born spotted owls into the wild is an essential component of the spotted owl recovery program,” said the minister in a written statement.

“It’s not without risk, and we acknowledge that there is much that we have to learn and discover so that we can support these owls to survive and become established in the wild.”

Hobart said the latest deaths should galvanize government to put more money toward field biologists who check in on owls raised in captivity. He also said the government bears some responsibility for allowing the logging industry to eat away at their old-growth habitat and open up space for the Barred owl, an invasive species, to encroach on the forests.

“They will actually kill a spotted owl and they'll eat all their food,” said Hobart, suggesting they be relocated to Eastern Canada where they are a red-listed species.

“We have to do more.”

On Friday, Jasmine McCulligh, facility coordinator for the Northern Spotted Owl Breeding Program, said her team has spent 15 years caring for a population of spotted owls.

“Although this is clearly not the result we had wished for, we are committed to learning as much as we can from this experience to help the breeding and release program move forward,” she said in a statement.

'A learning curve'

Hobart praised the dedication of government biologists and those working at the Langley breeding program but said money and geography can sometimes get in the way of a good idea.

“We’re all taking this hard,” he said. “It's all a learning curve.”

One solution would be to better train people in the Spô'zêm First Nation to check in on the owls. The chief said he’s also preparing to submit a proposal to the B.C. government to launch their own rehabilitation and breeding facility on their territory. That way, he says, they can directly access an old-growth corridor and fly back to the breeding centre if they need anything.

“It's right where they need to be released. Like this is crazy to have them being raised somewhere down where there's train sounds and all these other things and avian flu,” he said.

“We’ll work it ourselves. We know exactly the spot — right out the back door of it is old growth.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story indicated a third owl released into the wild died after being hit by a train. In fact, the owl survived and is recovering at a rehabilitation centre in Langley.