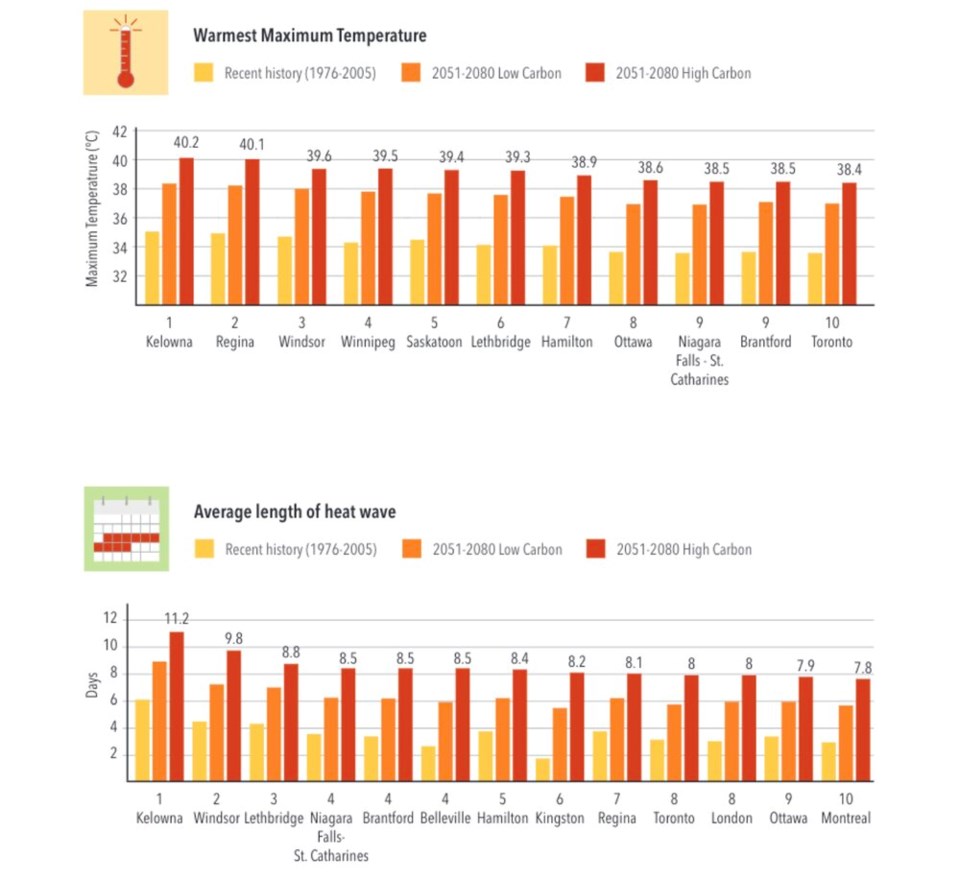

Kelowna is projected to face the longest-lasting heat waves and the hottest maximum temperatures of any major Canadian city, a new report says.

The report, published Wednesday from the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, outlines several measures tenants, landlords and communities can take to prepare for the .

Modelling heat waves between 2051 and 2080, the researchers found Kelowna will become among the top 10 “hottest” metropolitan areas in Canada.

Smaller Interior communities like Kamloops, Penticton, Creston and Vernon are also expected to reach similar temperatures.

In another metric, Windsor, Ont., is expected to have the most number of very hot days with an average of 78.8 days over 30 C under high-emission scenarios. In that field, Kelowna came in fourth after three other southern Ontario cities.

Over 17 million urban Canadians are expected to face extreme heat in the coming years. The report also warns of “red zones” in low-lying areas in B.C., southern Prairies, the St. Lawrence River valley in Quebec, and regions north of Lake Erie in Ontario.

Whereas flooding and wildfire — expected to increase in frequency and intensity this century — will cost Canada vast sums of money, heat waves will ramp up as a kind of silent killer.

“The impacts of heat are death,” said lead author Joanna Eyquem, managing director of Climate Resilient Infrastructure at the centre.

The parts of the country expected to be hit with the hottest heat for the longest aren’t always the most vulnerable. Heat waves that occur outside of the summer or in communities unaccustomed to extreme heat can face massive human casualties, as was seen in Metro Vancouver last summer when nearly hundreds died alone in hot, poorly ventilated rooms.

Eyquem called on all levels of government to start taking extreme heat more seriously.

After last year’s heat wave in B.C., Eyquem said she expected to see a growing recognition of heat’s deadly potential. But when she looked at Canada’s federal disaster database, it still failed to mention the disaster.

On a Health Canada webpage outlining its role in a disaster, Eyquem said the agency did not include extreme heat among other risks like earthquakes, floods and outbreaks of disease.

“It’s not seen as an emergency,” she said.

To date, local governments have largely been left on their own to deal with extreme heat — whether creating cooling centres or deploying misting fountains. But as the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, provincial and federal governments play key roles providing funding, coordinating action plans and delivering messages.

In the interim, an individual who chooses to adapt their home to extreme heat also makes life more comfortable and affordable at the same time.

And while the report doesn’t specifically target Indigenous communities or the acute challenges of Canada’s North, Eyquem says it offers a baseline for action at the local level.

“There are simple things, even just sticking up some window films to kind of cut the sun coming through your windows,” she said.

“That's very affordable. So I don't know why we're not doing that.”