High above the waters of the Fraser Canyon, James Hobart trudges up an old logging road and into the territory of the last wild-born northern spotted owl in Canada.

Chief of the Spô'zêm First Nation, Hobart has put his people’s weight behind saving the owl, the country’s most endangered bird.

He steps over a downed tree trunk, and wades through a trench — part of a series of barriers British Columbia’s government installed to block passage into this patch of old-growth forest.

Around a bend, six storey-high caged aviaries rise among trunks of Douglas fir and cedar. A year ago, government biologists released two male owls here in the first-ever attempt at captive breeding. The owls never made it through the first winter, their GPS collars found among their starved remains.

Hobart looks up at the empty cages. The first snowfall of the year crunches under his feet.

“We're living on dead land,” he said. “And we don't even know it.”

About 40 centimetres tall with dark plumage, dark eyes and no ear tufts, the northern spotted owl was first listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act in 2008.

Ranging from southern B.C. to northern California, biologists consider the owl an umbrella species, one whose home-range is so sweeping that to protect it means offering shelter for dozens of other species that call old forest home.

Known as skelúle蓙 in the Nlaka’pamux language, First Nations consider spotted owls “messengers of the forest,” a signal whose health reflects the wider ecosystem.

“This is an anchor relative for our nation,” Hobart said. “It’s a legacy.”

Today, that legacy is dangerously close to extinction.

Before European colonization, 500 breeding pairs once extended across nearly a million hectares of southwest B.C. The owls thrive in steep old-growth terrain, with their core critical habitat thought to have stretched in a triangle from Metro Vancouver as far north as Lillooet, and then back down the Fraser Canyon into the woodlands of the Fraser Valley.

Where once that territory supported upwards of a thousand owls, today, the survival of Canada’s wild-born population has dwindled to a single female, who lives high up in the Spô'zêm watershed in the territory of Hobart’s people.

Early failures to reintroduce captive bred owls have revealed duelling visions over what’s causing the bird’s near extinction — and how best to pull it back from the brink.

On one side, B.C.’s provincial government says it’s focused on the culling and removal of invasive barred owls, while breeding the endangered species back; on the other, a federal ministry and its backers, who say it makes no sense to release owls into a forest ecosystem when its integrity remains shattered.

For others, the owl’s fractured and faded habitat represents something bigger — a nation whose species at risk laws have failed the most obvious candidate for protection at a time scientists warn of a growing biodiversity crisis.

‘They chopped us up’

Over the last century and a half, the transitional old-growth forests where the owls have evolved have been eaten away to feed the development of cities and an endless rush for riches.

A highway sign leading into Spô'zêm territory reads “Gold Rush Trail.” Logging road switchbacks zigzag up the steep canyon valleys. Like the owl’s thick forest territory, the Spô'zêm people paid the price. The community now lives on a reserve made up of 16 disparate parcels of land, a colonial legacy leaving them caught between the highway and the railroad.

“They chopped us up, put us on both sides of the river,” Hobart said, sipping on a cup of coffee at the band office.

Dispossessed of their territory, the Spô'zêm held on to their stories. On camping trips with his siblings, Hobart’s mother would tell them bedtime stories about how spotted owls used to be human-like creatures who would carry off children who refused to go to sleep.

“It took too many kids and was turned into an owl,” said Hobart. “Now, it can only make the sound of a larger beast.”

In the decades since, that sound has gone largely quiet across the owl’s Canadian range, prompting the Spô'zêm to do whatever they can to save what habitat is left. That includes leaving gaping sections of road washed out after catastrophic floods hit the area in 2021.

A few kilometres from the band office, the thick forests of the Spô'zêm watershed scale the valley’s peaks. Somewhere in the trees above, skelúle蓙, the last wild spotted owl in Canada, endures.

Hobart stands on the edge of the road, cratered by a washout. This is where the logging trucks used to come, he said.

“We’ve been trying to make sure people don’t fix them,” said the chief. “So people don’t go up.”

It’s a small gesture in the last refuge of the species. Together with biologists and the environmental group the Wilderness Committee, Hobart has pushed Canada to stem what they say has been a provincial government “” approach to saving the spotted owl.

In February 2023, federal biologists presented Canada’s environment minister Steven Guilbeault with a threat assessment concluding that without an emergency order halting the issuing of logging licences, the survival and recovery of the spotted owl would become “highly unlikely” within less than a year.

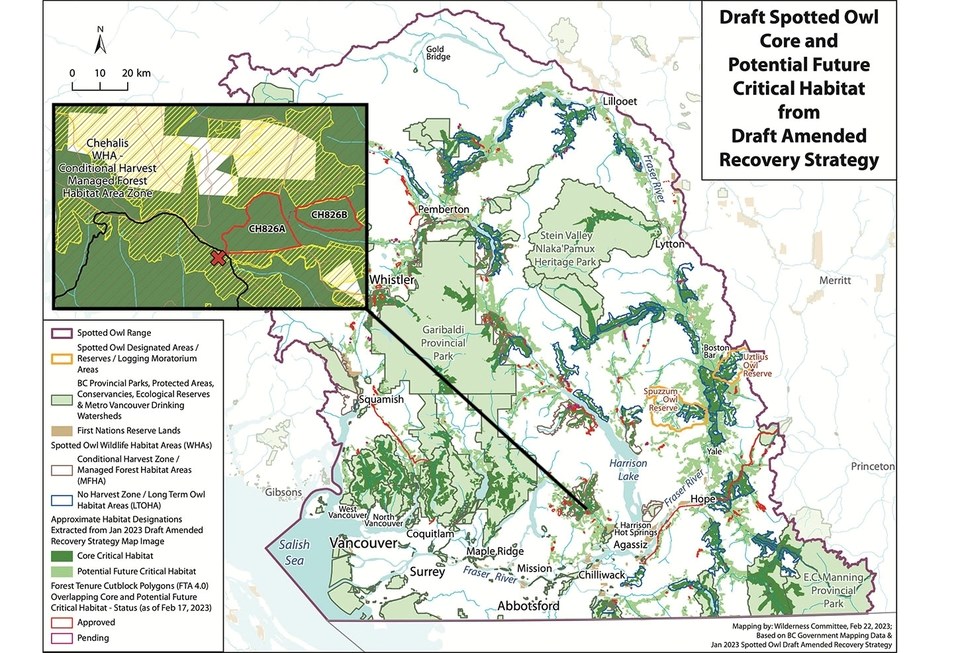

Guilbeault, who concurred with the assessment, said he would flex his authority under the Species at Risk Act and recommend an emergency order to cabinet to suspend logging on 2,400 hectares of critical spotted owl habitat scattered like shotgun pellets across the region.

When three months later, the environment minister had still not recommended the order, the Wilderness Committee sued Guilbeault, claiming the delay was unlawful. A week before the case was to be heard, court documents and a letter to First Nations revealed the minister had finally made his recommendation. Federal cabinet, whose deliberations are secret, had turned it down.

A week later, Wilderness Committee lawyer Kegan Pepper-Smith stepped into a Vancouver federal court and asked the judge to set future limits on how long Canada’s environment minister could delay a recommendation for an emergency protection order under the Species at Risk Act.

The ruling, which won’t be handed down until sometime in 2024, will likely come too late to impact spotted owl habitat, said Pepper-Smith.

Meanwhile, a growing body of evidence suggests logging continues on land the federal government has flagged to help recover the species.

‘That’s devastation’

West of Harrison Lake, a logging road slaloms through forested terrain, past a small lake, and up a series of steep switchbacks. To the left, burn scars from a recent wildfire obscure evidence of logging in 2022.

Minutes later, the washboard dirt roads flatten and the forest opens. Heavy machinery and trucks are perched on landings of freshly churned soil.

Nearly all the trees of cutblock CH826A, designated as a potential future home for owls, lie on their side — cut.

“To look at what they’re calling managed?” says Hobart. “That’s devastation.”

While Minister Guilbeault waited to recommend an emergency protection order to cabinet, documents show the B.C. government handed out a permit to a numbered company to log the cutblock on June 14, 2023.

The Wilderness Committee’s Joe Foy, who has spent decades monitoring logging in spotted owl habitat, says it’s just one more data point showing an increasingly fragmented owl habitat.

On the hood of his pickup truck, Foy spreads out a map of southwest British Columbia. He points to where we are: Chehalis Wildlife Management Area, a provincially designated area also flagged by the federal government as future critical habitat for spotted owls.

“This would have been ready for owls in 50 years, but you have to make the decision now to protect it,” says Foy. “The province is not f**king listening to the feds.”

A Ministry of Forests spokesperson acknowledged CH826A is part of core critical spotted owl habitat outlined in the federal government’s draft recovery plan.

The cutblock, added the spokesperson, also falls within future habitat for spotted owl managed by the province, but that “some timber harvesting is allowed provided it maintains attributes for spotted owl,” such as large-diameter trees.

Managed Future Habitat Areas, including CH826A, “were established as a contingency,” said the spokesperson in an email. “They use conditional harvest measures to safeguard options for future protections.”

In an interview, Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship Nathan Cullen said the province has protected more than enough old-growth forest to support the reintroduction of spotted owls for several years.

“Clearly, the limitation on our success right now is not limited by territory, because with 280,000 hectares — 700 Stanley parks — that's a sufficient territory to happily support the owls,” he said.

Cullen said he would “look into” any allegations that logging was occurring in land set aside for spotted owls. He said decisions on whether to log or protect future owl habitat would be part of “forest and landscape planning tables” announced in February 2023.

“That has always been my particular view. It’s a better way to go about things rather than polygon by polygon,” the minister said.

How much suitable forest B.C. sets aside for spotted owls has been grossly overestimated, says Jared Hobbes, a biologist and former scientific advisor of B.C.’s spotted owl recovery plan.

In a , Hobbes found only half the forests B.C. said it was protecting for owls was actually suitable habitat.

“What they've done is they've drawn these big boundaries that include a whole bunch of previously clear-cut areas that are not suitable for use by spotted owl right now,” Hobbes said.

Hobbes estimates that within the range of spotted owl, the province continues to approve logging on about 3,000 hectares of old growth every year. Aside from losing habitat, the industrial activity has also left fragmented islands of old growth with few connections to allow offspring to carve out new territory for the next generation, he said.

“I can find you hundreds of examples. But the point is the same: they're logging habitat that is needed for the recovery of this species,” said the biologist.

Federal biologists recognized the gap between what the owls need and what was being logged in their threat assessment. And while it failed to convince cabinet, Foy said it ultimately addressed the question: if everything is OK in the forest, why are we down to one owl?

“It's a very simple answer,” Foy said. “We broke the forest.”

Governments advance duelling views on what’s killing owls

Behind closed doors, a growing battle over how to protect and recover the spotted owl has played out in a flurry of correspondence between the federal government — which has recognized logging as the primary threat to the owl — and the B.C. government, which says invasive species and breeding more owls are the biggest hurdles.

According to federal court affidavits, a month after Guilbeault said he would issue an emergency order recommendation, the provincial government responded offering a two-year extension on logging deferrals in the Spô'zêm and Utzlius watersheds.

Shortly after, Cullen writes to Guilbeault to end his position that the spotted owl faces “imminent threats to its survival.”

In a memo, Guilbeault agrees and drops his immediate concerns around “survival.” The “recovery” of the species, however, still faces an imminent threat as long as the B.C. government continues to hand out “forestry licences and authorizations in areas of suitable future habitat,” the document says.

The closed-door conversations continue. In one letter, Cullen claims the federal government is relying on science “our ministry experts have found questionable” and that “habitat is in no way limiting or risking our recovery efforts for spotted owl.”

The biggest concern, said Cullen, are impacts from the Trans Mountain expansion project, which passes next to the Northern Spotted Owl Breeding Centre. Cullen writes that between 2019 and 2023, owl egg fertility at the breeding centre went down 39 per cent.

On May 12, B.C. filed a formal complaint to the Canada Energy Regulator, despite a December 2022 federal threat assessment that concluded construction on the pipeline was not producing acoustic disturbances that threaten the survival or recovery of the species.

When asked in an interview whether habitat destruction, and logging in particular, continued to threaten the owl’s recovery, Cullen did not waver.

“The measures in place right now are sufficient,” said the minister. “Right now, owl habitat is not the limiting factor on spotted owl recovery — getting more owls into the wild is.”

'You grieve for them’

Somewhere on a 10-hectare plot of farmland in Langley, B.C., 34 endangered owls swoop, perch and nest within the confines of cages. Some are only a few months old, still covered in downy white plumage. Others are old enough to sport their namesake spotted feather coat and are given room to practice hunting.

Like much of the carefully guarded facility, artificially incubated eggs are carefully monitored by camera. Once hatched, biologists and experts in husbandry begin to hand-rear the owls, says Jasmine McCulligh, who as facility coordinator, manages the day-to-day operations at the Northern Spotted Owl Breeding Centre.

Deciding which owls should be released only comes after they have survived their first year. At that point, they go through a battery of tests to narrow down the healthiest, most genetically diverse, and best hunters. The long-term goal is to release up to 20 owls from the breeding facility per year for the next 50 years.

“It’s never been tried before, except here,” said Foy. “This is the only one in the known universe. If it'll work? Don't know.”

The live breeding program has been a long time in the making. After the first six owls were brought to the centre from the wild in 2007, it took 16 years to release the first two males (the same ones that died last year). Another released owl was injured and returned to the centre after it collided with a train in the Fraser Canyon. Two more were released in September and will soon face their first winter in the wild.

“You grieve for them,” McCulligh said of the dead owls. “I was there for their first heartbeat.”

It’s hard to know what went wrong.

“No one has ever bred spotted owls,” said McCulligh. “We are trying to learn as much as we can from those individuals.”

The centre is now introducing live prey much earlier. But whether the latest changes will lead to greater success remains an open question.

McCulligh said the team still doesn’t have enough people to care for hatching owls in the spring while releasing older owls into the outdoor cages — the latter, a move that would give them more warm months to get used to the forests of the Fraser Canyon.

The species has shown a genetic instinct for hunting, according to McCulligh. But she says growing up in a crowded and closed environment can make adjusting to life in the forest difficult.

“Do you sit and wait here for X number of days? Or is it X number of days? They don't necessarily know that quite yet,” McCulligh said.

Echoing Minister Cullen, McCulligh said successfully releasing more owls and hitting back against invasive species — not a lack of habitat — was holding back the owl’s recovery.

Between 2007 and 2021, the province has culled or relocated 150 , what McCulligh describes as a hearty, highly reproductive invasive species that outcompetes the spotted owl for food and habitat.

“They'll eat everything that moves,” said McCulligh.

Logging led to owl’s downfall long before invasive species arrived, says biologist

In 1997, Hobbes was camping at S&M Creek, about 40 kilometres east of Pemberton, when a northern spotted owl swooped down out of the forest and alighted on an old-growth branch next to a logging road.

Hobbes turned his headlamp toward the bird, bathing it in a white light and illuminating its big round eyes.

“I was humbled by it. And I was honoured to see it. And I just wanted to share that feeling with people,” he says.

More than 25 years later, Hobbes has likely seen more wild northern spotted owls than anyone else in Canada. He has published everything from coffee table books filled with photos of the owl to academic papers and sweeping habitat maps for government.

For 15 years after that first encounter, Hobbes mapped protected areas for species at risk in B.C. and was the scientific advisor for the province’s spotted owl recovery program. One person who knows the biologist described how he used to track young owls through steep forest at night tens of kilometres at a time just to make sure they were healthy.

But in 2013, he left government, frustrated over what he says was an emphasis on captive breeding and a consistent misrepresentation of scientific consensus.

“They asked me to kill barred owls and they kept logging habitat. I said, ‘I can't do this. This is disingenuous. It’s not good science,’” Hobbes said.

Hobbes says the B.C. government’s argument falls down when you consider research on the U.S. side of the border, where declines in spotted owls tracked with habitat loss long before the arrival of the invasive barred owl.

He says when spotted owl forest habitat is destroyed or degraded, the bird is forced to increase its territory size, and burn more energy to hunt. Eventually, that leads owls to starve and wink out.

Those who survive find it increasingly hard to find a mate, Hobbes said.

“They keep moving the barred owl to primary threat and logging to secondary, and I keep saying, ‘Nope, put it back. Logging, primary. Barred owl, secondary,’” the biologist said in a recent interview. “There's been decades of research.”

“We don't know why they won't acknowledge the evidence that's in front of us.”

When needed most, Canada’s species at risk law failed

In recent weeks, the B.C. government said it would put up hundreds of millions of dollars to redefine how forestry is done in the province in what one environmentalist described as the “missing ingredients” in protecting old-growth forests in B.C.

On Oct. 26, $300 million was set aside for a that will help build alternative economies so First Nations can make money without harvesting old-growth trees.

Last week, the federal and B.C. governments, along with Indigenous leaders, said they had agreed on a to finance the protection of 30 per cent of B.C.'s land by 2030.

“In B.C., we may have burst a dam,” said Ken Wu, executive director of Endangered Ecosystems Alliance.

On big picture conservation targets, Wu says B.C. has made “leaps and bounds” in recent weeks. But big loopholes remain, he said. The province has not set conservation targets for medium-scale ecosystems, let alone species.

“If you don’t have ecosystem-based targets, it’s like a surgeon that doesn’t distinguish between organs,” Wu said.

That approach risks protecting uncontested landscapes, like alpine and subalpine environments, over the big-treed forests of lowland valleys where industry and conservationists often collide.

“It’s on the species level where the province has been the absolute worst,” Wu said.

More worrying, said Hobbes, is that those advocating for endangered species have nowhere left to go. He always saw Canada’s Species at Risk Act as a last backstop, a big red button that when pressed would trigger a sweeping response for any creature at risk of disappearing forever.

The owl tested that law, ultimately revealing it has the weight of a ‘paper tiger’ when it was needed most, Hobbes said.

If the federal law won’t trigger protections for spotted owl — the “best-case” candidate, according to Hobbes — he says there's no hope for all the other less enigmatic species like the Haida Gwaii slug or more complicated endangered species like caribou.

“If we can't win this battle for spotted owl, we're done,” said the biologist.

“We need to rewrite the law.”