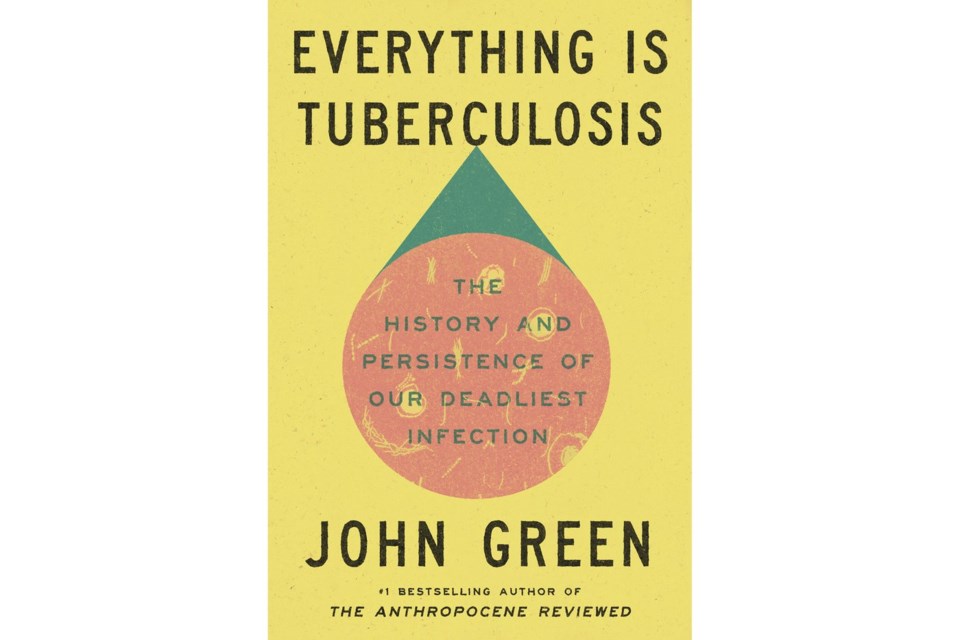

So you read or watched John Green on YouTube, and, if you’re like me, you probably thought, “I would read or watch anything this mind produced for public consumption.” Even if it’s a 200-page nonfiction thesis on tuberculosis arguing why it should be Public Enemy No. 1 and on its way to eradication.

Because, in true fashion, there’s a footnote on the copyright page explaining the reasoning behind the font choice for his newest book, “Everything is Tuberculosis.” (Spoiler: The reason for the font is tuberculosis. Everything is.)

Early on, Green establishes that the tuberculosis is the top killer of humans among infectious diseases — a longstanding status quo only briefly disrupted by COVID-19. The slow-moving in one year and killed about 1.25 million, according to a recent World Health Organization report.

Yet, as Green shows throughout the book, TB is curable and even preventable.

The text seamlessly moves through related topics, from TB’s effects on history and fashion to the socioeconomic inequities that perpetuate the disease, and even the romanticization of an illness that, for a period, was associated with soulful poets and delicate feminine beauty.

But this synopsis will seem bone-dry compared to the actual text, because the real magic of Green’s writing is the deeply considerate, human touch that goes into every word. He uses the stories of real people to turn overwhelming problems into something personal and understandable. “We can do and be so much for each other — but only when we see one another in our full humanity,” Green writes.

“Everything is Tuberculosis” is reflective and earnest, with a few black-and-white pictures to illustrate a point or put a face to a name. Little nuggets of personalization consistently bring us back to our shared humanity, even in footnotes.

When considering “patient noncompliance,” Green discloses his own diagnoses and wrestling with taking prescriptions. This compared with patients in Sierra Leone who, unlike Green, often struggle to get to the clinic to obtain their medication, or can't afford enough food to take it without getting sick. On the other hand, some of their struggles are the same, side effects from pills and stigma around illnesses being some of the most common reasons patients might diverge from their prescribed course of medication, regardless of access.

As one might expect from Green, the book is weirdly touching and super quotable. “Everything is Tuberculosis” is rich with callbacks that help underscore ideas, wit and humor that foster learning even alongside more somber bits.

Green offers many reasons why he became obsessed with TB, but none brought tears to my eyes so unexpectedly like the stunningly apt metaphor comparing writing to the pool game “Marco Polo.” The explanation references TB activist Shreya Tripathi, who had to sue the Indian government to get the medication that would have saved her if it hadn’t taken so long to get ahold of it.

Despite the death and harsh realities, it is a hopeful book overall.

Green takes stock of the history, looking at the vicious and virtuous cycles that led humankind to where we are now, posing a challenge and a question rolled into one: Which type of cycle will we foster?

___

AP book reviews:

Donna Edwards, The Associated Press