John Horgan didn’t really want to be premier. And maybe that’s why he was such a good one.

Only a guy who turned down the job of party leader repeatedly, who wanted another generation to step up and take it on, who had to have his arm twisted to lead, could excel at a job where the immense power so frequently turns otherwise good people into shadows of themselves.

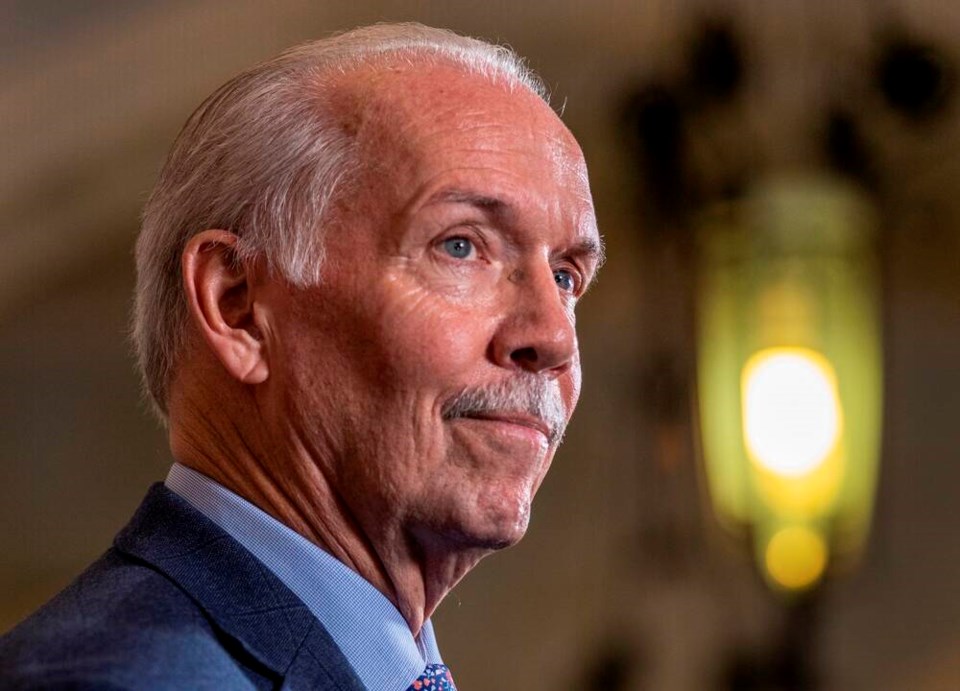

But not ‘John from Langford,’ as he often called himself, or ‘Premier Dad’ as he was known to his staff. Horgan had the rare distinction of actually becoming a better politician, a more authentic version of himself, as he settled into the pressure cooker that was the province’s top job.

His of cancer at the age of 65 was heartbreaking to friends, colleagues and the province. But his legacy as the greatest premier the BC New Democrats have ever seen, and one of the most popular premiers in provincial history, is a remarkable story of a person stepping up to meet the moment and realize their true potential.

To understand Horgan’s journey, you have to first remember the bespectacled, bearded, curmudgeonly version of Horgan that skulked the hallways in opposition, inexplicably picking fights with people after being elected in 2005.

That John Horgan regularly clashed with critics. He’d start shouting at BC Liberal government staffers who’d come to monitor his press conferences. He’d turn his chair around to show his back to then premier Christy Clark after asking her a question in the legislature. He’d grow indignant at reporters who challenged him, sometimes questioning their motives, professionalism and intelligence before storming out of interviews and off down the hallway.

But after every clash, he would inevitably phone, text or email an apology. The moment got the better of him, he would say, and he was sorry for the outburst. It was hard to hold it against him.

Horgan’s secret weapon was his authenticity. Yet, for years, it was also his curse.

“The prospect of the constraints of message boxes and having to check with other people — I’m going to say stupid things and I’m OK with that,” Horgan said in 2013, as he ruled out a bid for BC NDP leader. “But as leader you are under so much scrutiny I believe that would constrain my ability to add to the debate about where we need to go as a party.”

It took a lot to get him to reconsider a leadership bid, including a phone call from then presumptive frontrunner David Eby, as well as arm-twisting from longtime friends Carole James and Maurine Karagianis.

“I think you have what it takes to win and I would be glad to be, if you want me, your campaign chair,” Eby told Horgan in a phone call.

“John, you are our best hope,” added Karagianis.

Horgan wanted a younger candidate. But none stepped forward. At his campaign launch for leader in 2014, he joked: “I’m the younger generation I was looking for.”

Still, the NDP suffered through “Angry John” for years as opposition leader. It wasn’t until halfway through the 2017 election campaign, after he blew one of the televised debates, that Horgan saw the light.

Horgan had been particularly chippy during that debate, and snapped at Clark when she put his hand on his arm and said, “Calm down, John.”

“Don’t touch me again, please,” Horgan said. “Thank you very much.”

He later sneered at Clark during one of the long answers.

“If you want to keep just doing your thing, I’ll watch you for a while — I know you like that,” he said.

It was awful. It was also a turning point.

“That was the lowest point,” said Horgan. “When I went back to the hotel after it was a gut check time. I have let a whole lot of people down by being overly passionate, overly responsive to prodding.”

Horgan and his senior advisors, including Bob Dewar and Marie Della Mattia, helped channel Horgan’s anger into a more usable political vehicle.

He spent the last half of the campaign transforming from “Angry John” into Horgan the “Happy Warrior” whose temper (rephrased as passion) could be linked to things like the price of child care, the cost of a home, the tax breaks for the rich, and the treatment of the most vulnerable under the Liberal government.

The rebrand fit, like a piece of the puzzle falling right into place.

People suddenly saw a guy they could relate to. He was upset at the things that upset them. Occasionally he said something stupid, but in an aw-shucks kind of way. It somehow made him even more endearing. He seemed to mean well, even when you disagreed with him. He suddenly met the important litmus test of a politician you’d like to have a beer with.

Horgan rose up in the latter half of the campaign to meet the moment as the “Happy Warrior.” He bridged the gap between the working-class New Democrat voter, and a new class of urban progressives. He carried the NDP to a near-tie result, then carried the party again into a power-sharing deal with the BC Greens that toppled the Liberals.

After becoming B.C.’s 36th premier, Horgan’s popularity only grew. The Horgan brand, and the loyalty it engendered amongst the public, allowed the NDP government to not only stickhandle contentious issues like the COVID-19 pandemic, but also win a massive majority in the snap 2020 election.

The Horgan you would meet in the hallways of the legislature when he was premier — often giving some sort of impromptu tour to locals or just kind of hanging around — was a far cry from the Horgan of previous years. Rather than crack under the pressure of being premier, he flourished.

I spent a lot of time with John Horgan over 16 years covering politics, and saw him evolve from his first term to his last, when he retired due to throat cancer in 2023.

My colleague Richard Zussman and I interviewed him extensively for our book . One quote from an interview he gave us stands out in particular.

“I haven’t waited my whole life to become premier,” Horgan said.

“I waited a few years to become premier, because I never aspired to do the job.

“But I have to say I was ridiculously serene, because the series of events that started with the calling of the election were really an opportunity for me to not be the person you observed as leader of the opposition but to be myself.”

In the end, that’s all Horgan needed.

His mix of passion, bluntness, humility and authenticity will be studied by politicians of all stripes for many elections to come. They’ll seek to emulate him, to try and capture that magic sauce that made him so successful. But as Plato wrote, “Only those who do not seek power are qualified to hold it.”

In that, John from Langford, the guy who never wanted to become premier but ended up being one of the greatest in provincial history, was truly one of a kind.

Rob Shaw has spent more than 16 years covering B.C. politics, now reporting for CHEK 撸奶社区 and writing for Glacier Media. He is the co-author of the national bestselling book A Matter of Confidence, host of the weekly podcast Political Capital, and a regular guest on CBC Radio.